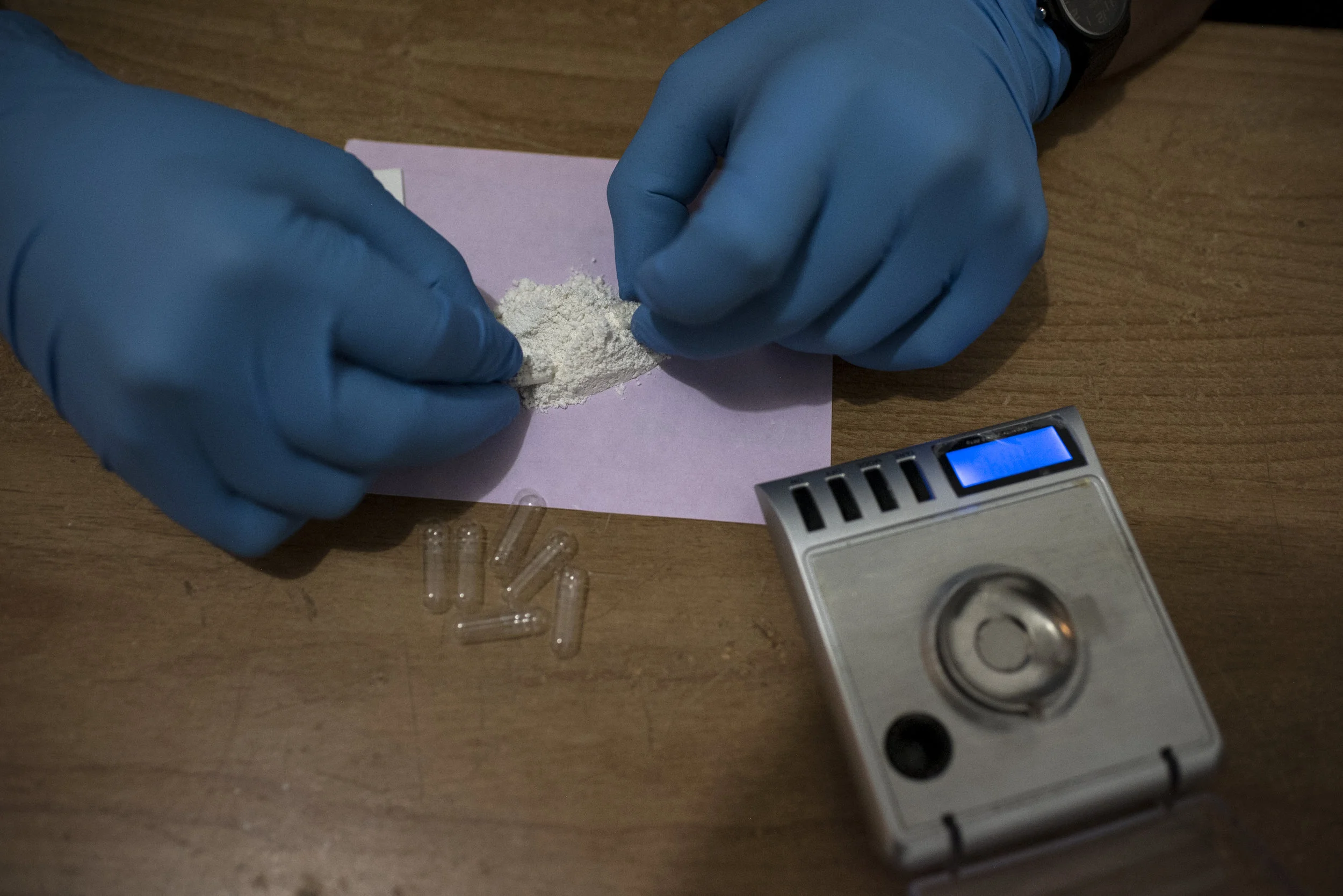

In the last house on a dead end street in Rosarito, Mexico, opioid addicts are getting treated with a psychotropic drug called Ibogaine that studies show is more effective than anything else in alleviating opioid withdrawals and curbing addiction.

But the drug is illegal in the U.S., and for the addicts who make it here, this is often a final, desperate attempt to get clean. The Ibogaine Institute is the last house on the block.

Emily Albert has been using opioids since she was 14 when she had minor surgery on her big toe after a basketball injury and the doctor prescribed Percocet for the pain.

Two days before Albert came to the Ibogaine Institute for treatment she was coming off a stretch of homelessness, barricaded in a hotel room north of San Diego. She wasn’t answering the door or her phone and an employee from the clinic, sent to pick her up, feared she might have overdosed.

When she finally did answer, a brief standoff ensued.

“She’s going to have to leave with you or leave with the police,” Thom Leonard, the institute's owner, told the employee over the phone.

Albert chose treatment.

While Ibogaine shows a great deal of promise, it comes with risks. People have died while taking it. Between 1990 and 2008 nineteen people are known to have died within 72 hours of taking Ibogaine. But researchers at NYU looked at autopsy and toxicological data from those deaths and found that most patients had pre-existing cardiac or liver conditions or still had opioids in their system, all of which are contraindications for Ibogaine.

On Ibogaine Ortega saw visions of his childhood. He saw himself as a baby and remembers seeing his abusive father, “his real mean face and he was just looking at me really mean,” he says.

Now, with a few days clean and at a point when his withdrawals should be at their worst, Ortega says he feels no desire to get high. No cravings. For the first time in years he says he feels like everything is okay.

Dr. Thomas Kinglsey Brown is an anthropologist and chemist at the University of California, San Diego.

In a study spanning eight years Brown tracked outcomes for addicts who were treated with Ibogaine.

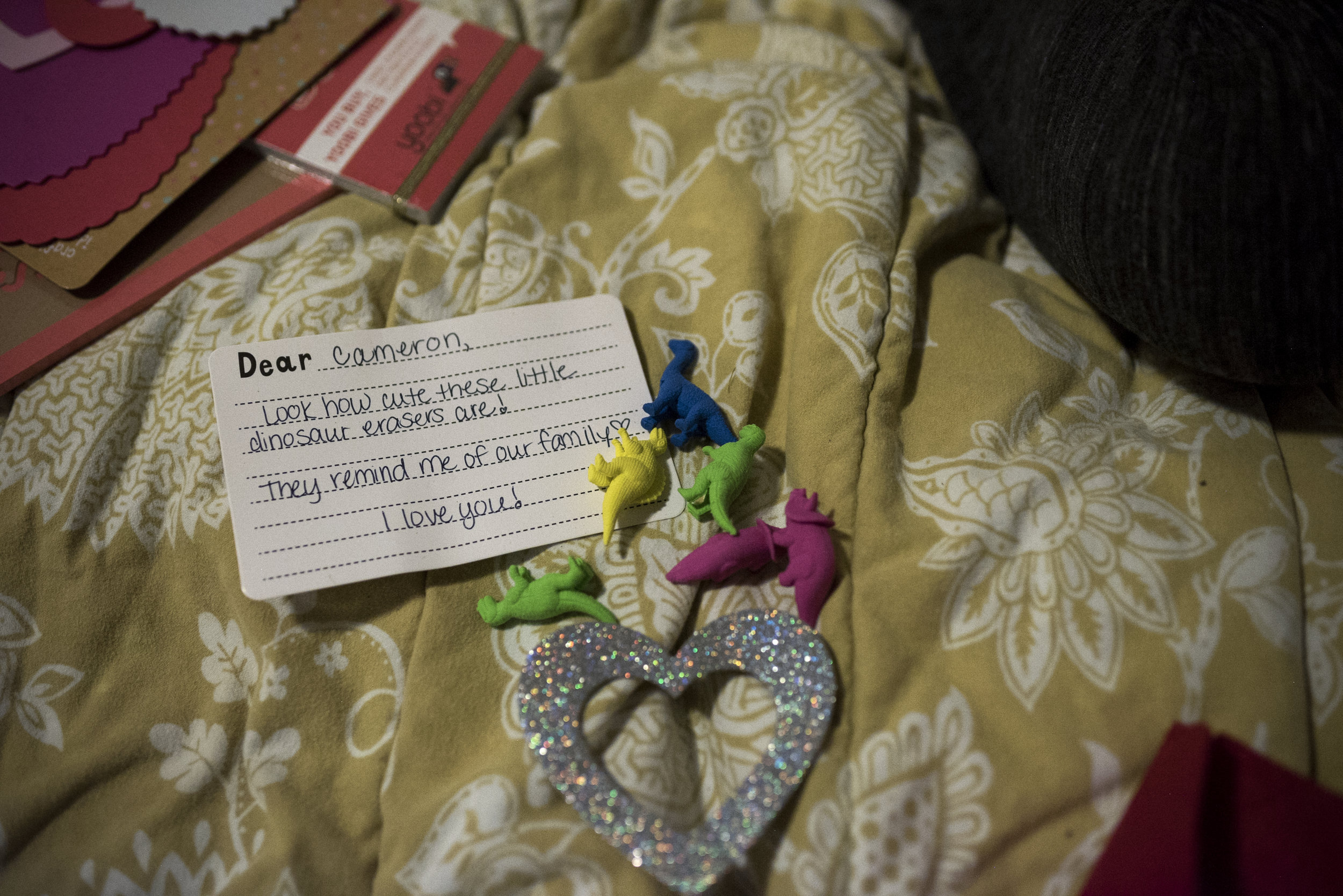

He says, not only was the severity of their addictions reduced throughout a 12-month follow-up period, their relationships with family and loved ones improved as well.

Moments after emerging from her 24 hour Ibogaine treatment, Emily tears up recalling a vision she had of her son.

“I could just tell that he was older and going through whatever I’m going through. It was like, basically if I don’t do this then he’s going to have to.”

A 2008 study in mice found that Ibogaine increases the level of a brain protein called GDNF which prevents the development of addiction.

GDNF allows new connections to form in the brain, essentially rewiring the brain and allowing individuals to form new, healthier habits.

But people familiar with Ibogaine’s use in treating addiction believe the psychedelic experience is critical to the treatment.

The Ibogaine Institute is one of a handful of clinics that pair Ibogaine treatment with ayahuasca, a plant derived psychedelic from Latin America.

“If Ibogaine is you telling yourself that you’re screwing up then ayahuasca is your grandma telling you you’re screwing up,” says Leonard, describing the very introspective experience of Ibogaine versus the more outward focused experience of ayahuasca.

Edgar Jimenez, the shaman, says ayahuasca helps improve your relationship with people in your life.

"I can't change how people treat me but I can change how it makes me feel."

Albert says she revisited childhood memories and had visions of her son.

Leonard is slowly expanding his clinic into adjacent homes, moving down the street away from the dead end. As Ibogaine creeps into the mainstream, he hopes he can reach more people and no longer be the last house on the block.